The effects of water scarcity are worsening in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region as projections indicate increasing demand over the next quarter-century. It is estimated that an additional 25 billion cubic meters will be needed annually, equivalent to the production of 65 desalination plants like Ras Al Khair in Saudi Arabia. This situation impacts public policy decisions, particularly regarding the rational management of water reserves and the initiation of large-scale projects aimed at serving businesses and populations. Now, every project must rely on sustainable solutions and encourage users to reduce consumption while adhering to budget constraints and operational balance.

The report titled “Economic Aspects of Water Scarcity in the Middle East and North Africa: Institutional Solutions” outlines the pricing, operational, profitability, and equity issues related to water supply and proposes a new approach to water management. This approach would be entrusted to specialized providers, national bodies, and communities, which would be granted additional powers to organize the distribution between agriculture and the population and involve citizens.

Capturing, transporting, or distributing water requires technological, health, and social skills. Responsibility for water resources is collective, involving suppliers, investors, and consumers. Pricing policies are the first lever of engagement. There are mechanisms for minimum volume and cost that reflect the desire for equitable distribution.

Andrea Barone, a co-author of the report, is an economist and digital development expert at the World Bank, specializing in market analysis and transparency promotion. His colleague, Edoardo Borgomeo, works in the Water Management under Climate Constraints Division. A former member of FAO, he specializes in water resource planning. Finally, Dominick de Waal and Stuti Khemani are economists at the same organization. The former focuses on water service financing and performance, while the latter conducts research on public policy innovation and is the author of “Making Politics Work for Development: Harnessing Transparency and Citizen Engagement.”

Addressing the Urgency and Revising the Public Framework

The MENA region faces extreme water scarcity, leading consumers, whether individuals, industries, or farmers, to consume the fragile water reserves without caution. At this rate, within five years, the minimum threshold of 500 cubic meters per person will no longer be guaranteed.

The situation worsens with demographic growth projections. The MENA region had 100 million inhabitants in 1960, compared to just over 450 million today, and over 700 million expected by 2050.

The distribution of available water faces a dual urgency: supplying the population without harming the agricultural production apparatus, which is essential for food security.

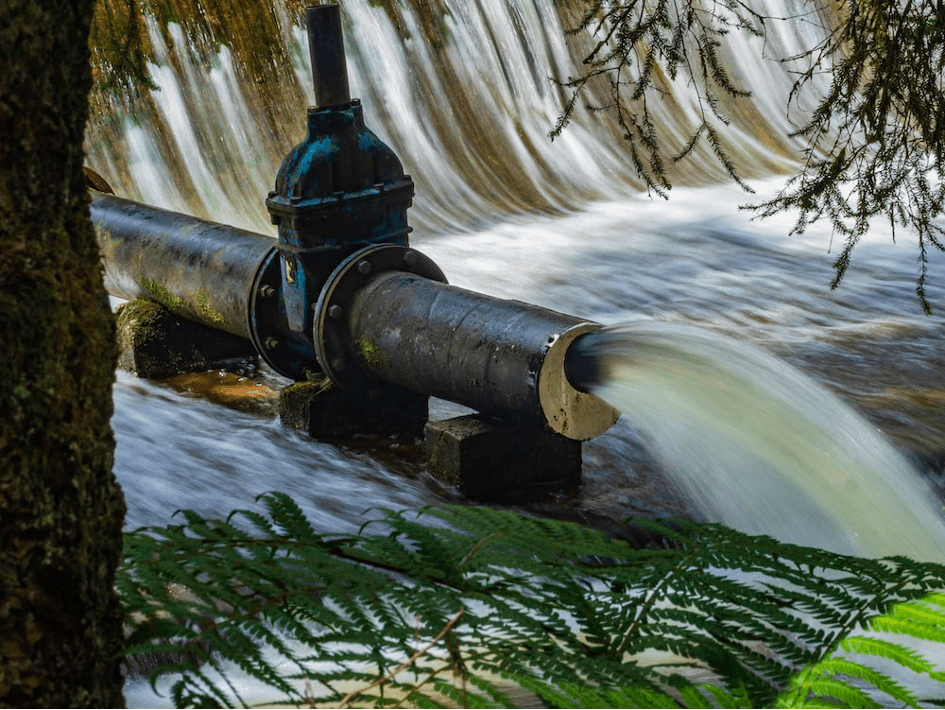

To avoid a “water war,” public authorities are trying to increase water capture solutions:

- Construction of new dams

- Groundwater capture

- Acceleration of desalination plants

These priority mega-projects overshadow expected transitions toward sustainable resource management and the protection of natural areas and biodiversity.

Once completed, these projects will provide additional supplies but will not solve existing problems of losses and waste. In the MENA region, water operators note that one-third of the distributed water is not billed, some of it is lost in transportation, and the rest is likely consumed illegally.

Additional infrastructure (dams and plants) provides an opportunity for increased environmental impact and postpones the transformation of public policies related to natural resource management.

Urgency justifies the development of new solutions, albeit not without environmental risks. Desalination, for example, generates marine discharges and locally alters the ecosystem.

More Equitable Water Distribution

The allocation of water resources primarily occurs between populations and the agricultural sector. Potential trade-offs are managed by centralized institutions with limited visibility into local specifics. Hence, the authors of the report propose delegating these decisions, and more broadly, the responsibility for service, to local authorities and delegates.

Transferring the distribution of water to local authorities and delegates ensures better alignment with resources, constraints (geographical, climatic, structural, etc.), installations, and local needs.

Reforming in this direction would improve users’ trust in operators and reduce their distrust of tariff or usage decisions made by central administrations.

According to the report’s authors, transparent and legitimate water management promotes research, facilitates data access, and stimulates innovation and financing. Operators can improve infrastructure management (pumping, distribution, collection, treatment) by incorporating sustainability goals.

Involving Users

Users also play a role in how they use water resources. States must communicate with the public to encourage individual contributions through reduced and more responsible consumption.

For example, South Africa conducted a public communication campaign as part of a new strategy. The operation involved real-time broadcasting of consumption data with the aim of changing habits or enforcing restrictions.

Unlike tariff policies seen as directives, calls for citizen initiatives are better accepted, even though a majority expects the state to cap tariffs.

A Necessary Transition

Despite climate change, the Middle East and Africa must deal with population growth and economic development, obliging them to envision a new water distribution paradigm.

The proliferation of infrastructure meets short-term needs but accelerates the depletion of resources.

Before producing more drinking water, distribution and consumption should be improved by prioritizing community interests, minimizing waste or pollution-generating solutions, and directing tariff strategies.

Water stress is a lever for transition, as public authorities fear the political instability caused by scarcity, and regions fear its impact on their development.

This resource crisis, coupled with environmental ambitions, presents an opportunity for states to change their management model.

Source : World Bank