Responding to the needs of both buyers and sellers, international trade in agricultural products is age-old. Some distribution networks and routes are short-lived, while others can last centuries before they are disrupted by a new reality.

There is no disputing the importance of international trade in agricultural products throughout history. One need look no further than the spice trade which made the fortune of Venice, the importance of the Port of Odesa for exporting cereals in the days of the Russian Empire, the exploitation of colonies as a way of feeding major cities on the cheap, or the Marshall Plan, which was aimed at European countries devastated by the Second World War.

There is no disputing the importance of international trade in agricultural products throughout history. One need look no further than the spice trade which made the fortune of Venice, the importance of the Port of Odesa for exporting cereals in the days of the Russian Empire, the exploitation of colonies as a way of feeding major cities on the cheap, or the Marshall Plan, which was aimed at European countries devastated by the Second World War.

With greater capacity driven by new means of transport, demographic growth and increased consumer purchasing power, trade in agricultural products has expanded considerably over the past few decades. All continents and most countries have benefited from it.

Because of the size of volumes traded as well as the unequal bargaining power between parties, major powers always benefit more from these trading relationships. It is therefore no surprise that “green power” has often tainted international agricultural trade. Major exporter countries as well as, on occasion, importers, have sought to use to their advantage the economic heft which their position on these markets has offered.

Growth of agricultural production and explosion of world trade

International agricultural markets are held in equilibrium between supply and solvent demand, where the price governs this equilibrium. Because of unpredictable weather conditions, this equilibrium is not always easy to find, as quantities produced may vary considerably from one year to another, while demand is hardly stable either. However, apart from in exceptional circumstances[1], annual carryover stocks are rarely excessive and, at least since the Second World War, major excess producer countries have found buyers ready to purchase these stocks.

When the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was created in 1945, it offered (under certain conditions) access to foreign currency resources to countries which previously did not have any. In this way, it also provided them with access to international markets. And from 1947, the GATT agreements[2] gradually lowered customs barriers, and thus barriers to trade. Had these institutions not seen the light of day, there would have either been cascading bankruptcies or serious shortages. This never happened.

Brazil, China’s farm

With a population of 1.4 billion but less than 10% of total world farmland, China’s food needs are immense. As the “world’s workshop”, it is currency rich. It can therefore import whatever it needs to satisfy members of its new middle class, whose incomes are growing rapidly.

The Chinese government had already committed to providing food autonomy for its people. Agricultural production has increased considerably since the dark days of the famine under Mao Zedong. Now, China is more or less self-sufficient when it comes to cereals. But it is still far from meeting its own needs for other agricultural products. And its needs seem limitless.

The Chinese government had already committed to providing food autonomy for its people. Agricultural production has increased considerably since the dark days of the famine under Mao Zedong. Now, China is more or less self-sufficient when it comes to cereals. But it is still far from meeting its own needs for other agricultural products. And its needs seem limitless.

In this way, China has become the world’s biggest importer of soybeans for its pork and poultry livestock. It also imports large quantities of dairy products from New Zealand and the European Union, maize from Central America and Ukraine, wood from Africa and Russia, not to mention pork since its herds were devastated by disease.

For its part, just a few years ago, Brazil had vast, fertile spaces that went unfarmed or were covered in forests. Thanks to an active policy, the country has developed its agricultural production well beyond its own needs. It exports its products throughout the world but has a special relationship with China, towards which it exports massive amounts of soybeans and meat.

The 2019 trade war between the United States and China played into the hands of Brazil and Argentina, which increased their soybean exports to China. However, the swine flu which has hit Chinese herds hard could temporarily reduce its purchases.

Brazil agri-food exports Unit: million tons

| Soybean exports | 2000 | 2010 | 2017 |

| Total

Of which to China

|

11.5

1.8 (15%) |

29.1

15.9 (55%) |

68.2

53.8 (79%) |

Source: FAO

| Meat exports (beef, pork, chickens) | 2000 | 2010 | 2017 |

| Total

Of which to China |

1193

19 (2%) |

4803

123 (3%) |

5699

647 (11%) |

Sources: FAO

The recent development of Brazilian agricultural production has occurred in parallel with the growth of Chinese imports. These two countries are thus tied to one another to satisfy food export capacity for one and supplies for the other.

The Black Sea countries providing for the needs of countries with a cereal deficit

Countries in the Maghreb and the Middle East have a structural cereal deficit. This deficit is growing. Sub-Saharan Africa imports wheat and rice too, to feed its major cities. For decades, exports from Europe and the United States were able to meet this demand. That is no longer the case.

Luckily, after twenty years and many disappointing harvests, the Black Sea countries – Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan (and also Romania) – have finally managed to increase their cereal production well beyond their own needs. They now have a considerable surplus. As their other production costs are very low, they are easily competitive on these relatively nearby markets.

International exports Unit: million tons

| Black Sea country exports | 2000 | 2010 | 2017 |

| Total | 7.6 | 27.8 | 70.2 |

*Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan

| North African country imports * | 2000 | 2010 | 2011 |

| Total

Of which Black Sea country exports |

25.5

0.17 (1%) |

36.0

1.1 (3%) |

44.0

15.1 (34%) |

* Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt

| Middle Eastern country imports * | 2000 | 2010 | 2017 |

| Total

Of which Black Sea country exports |

29.4

0.7 (2%) |

35.3

7.4 (21%) |

42.8

10.2 (24%) |

* All Middle Eastern countries up to Iran, not including Turkey

Sources: FAO

These imports need to be financed. Petrol-producing countries have the necessary resources. Others, such as Morocco, Turkey or Israel are increasing their production of fruit and vegetables which find profitable markets in Europe.

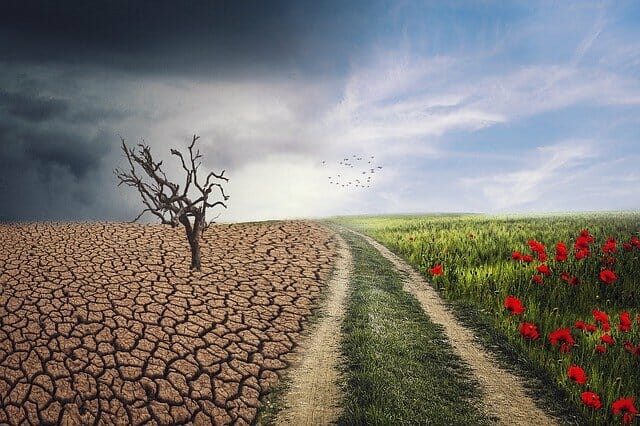

It would seem that the Black Sea countries have the capacity to increase their cereal production further still. This represents an opportunity for all the countries with a cereal deficit, many of which are threatened by increasingly frequent droughts and some of which are seeing their populations grow rapidly. These countries will inevitably need to turn to international markets more and more.

For many of the countries with a cereal deficit, their dependency is a weakness. It is however a commercial opportunity for the Black Sea countries, whose potential for production is huge. But, beyond the commercial opportunities, it would not be difficult to imagine a country such as Russia exploiting the situation to impose its political will over certain major clients.

Will sub-Saharan Africa have to depend massively on imports to feed itself?

The major food challenge of the 21st century will be feeding sub-Saharan Africa. Its population has already grown fourfold in sixty years. It is set to double by 2050. Will these countries be able to feed their populations by their own means when climate change may put some of them at a disadvantage?

There is a lot of space in Africa, some of which is uncultivated or under-used. Since the independence period, in 1960 or thereabouts, farmers have greatly increased the surface area of their farms. The subsequent increase in production has made it possible to feed a much larger population. But this has come at the expense of forests and, especially, fallow land, which is necessary to restore soil fertility. This process cannot therefore continue indefinitely. However, yield per hectare has only increased very slowly, irrigation has not made any progress, and farming methods have hardly changed, except for industrial crops such as cocoa, coffee or cotton.

There is a lot of space in Africa, some of which is uncultivated or under-used. Since the independence period, in 1960 or thereabouts, farmers have greatly increased the surface area of their farms. The subsequent increase in production has made it possible to feed a much larger population. But this has come at the expense of forests and, especially, fallow land, which is necessary to restore soil fertility. This process cannot therefore continue indefinitely. However, yield per hectare has only increased very slowly, irrigation has not made any progress, and farming methods have hardly changed, except for industrial crops such as cocoa, coffee or cotton.

Granted, Africa still has available land which may appeal to Chinese, Indian or even Western investors. These investors, however, plan to use this land for their own profit rather than feeding local populations.

Average world yields Unit: quintal per hectare

| 1961 | 2011 | Difference over half a century | |

| Millet | 5.9 | 8.7 | (+47%) |

| Sorghum | 8.9 | 15.3 | (+72%) |

| Wheat | 10.9 | 32.0 | (+194%) |

| Maize | 19.4 | 51.8 | (+167%) |

Note: Millet and sorghum are cereals mainly grown in Africa, which is obviously not the case for wheat and maize.

Source: FAO

Is sub-Saharan Africa ready to turn the corner towards intensification? A fully-fledged revolution in farming methods would be required. It has started, but it is still too slow or limited to a few select regions. It is true that most of the crops it produces have hardly been subject to genetic improvements carried out by researchers[1].

African countries already import wheat, maize, rice and dairy products to supply major cities. If this new “green revolution” comes too late, most of these countries will be forced to considerably increase these purchases on international markets. But will these markets be able to respond to such demands? Again, it will no doubt be the Black Sea countries which will be best-placed to offer a positive response. This will bolster Russia’s power, especially given that, if this hypothesis is borne out, market prices could soar, while many African countries lack the financial resources for such purchases.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the race is therefore on between the food needs generated by population growth and efforts to intensify agriculture, a race arbitrated by international markets.

Some modest trade, but very fragile

For the past few decades, roses from Kenya, Ethiopia and Columbia have decorated European homes. They are grown by big businesses, but they also provide welcome income for many employees in these countries. All these flowers are transported by cargo planes to the Aalsmeer flower auction in Amsterdam, from where they immediately travel off again towards various European countries. It is a thriving inter-continental trade but one whose products are not a necessity for buyers. What, then, are its medium to long term prospects, given that it relies on a complex logistical chain with high fossil fuel consumption?

The same observation could be made for imports of out-of-season fruits or vegetables. If the fight against climate change is taken seriously, will we still see strawberries from Israel on our markets in winter or pears from Chile or green beans from Burkina Faso?

* * *

Agricultural products travel a lot, and sometimes very far. But these trading relationships, albeit advantageous for both parties, are not always equal. This is because exporters may be tempted to take advantage of a position of strength to move into new markets (which is normal) but also to impose their rules on buyers (which is less so).

With enormous surpluses, particularly in cereals, Russia and Brazil may be tempted to gain unfair advantages. On the other hand, with China a massive importer of agricultural products, it may be tempted to impose its conditions on sellers.

“Green power”, which the US has long been accused of profiting from, is a temptation which is sometimes difficult to resist.

For the trade in agricultural products to be carried out under reasonable conditions, it must happen without any constraints or pressures of a political nature. It is the job of international organisations to see that it does. The multilateralism encouraged by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) aims to facilitate these trading relationships. The current return to bilateral agreements, advocated by the United States, can make them

[1] This stands in contrast to the “green revolution” which many Asian countries underwent from the 1960s to the 1980s, which was preceded by significant improvements in seeds of plants such as rice, maize or wheat.

Let us review a few particularly noteworthy examples of complementarity which characterise the trade of agricultural products.

[1] However, we shouldn’t forget the time when Brazilians had to resort to using coffee as fuel for steam engines during the great crisis of 1929-1935. And throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the European Economic Community was forced to stock mountains of butter and beef before selling them off for next to nothing.

[2] The GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade). This was replaced by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1995, with more extensive objectives and a dispute settlement system.