Access to financing remains a major issue for farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. The lack of credit availability is considered a central obstacle, if not the most significant one, to the expansion, modernization, and diversification of production, as well as the adoption of innovations. The recognition of the crucial importance of supporting small-scale farming in Africa is expected to strengthen in the coming years. The aim is to meet the financing needs estimated at $200 billion per year. Agricultural financing policies should be re-legitimized to address the numerous imperfections in financial markets. Public and private funds, including those from development agencies, foundations, companies, and NGOs, sometimes carrying innovations, should be channeled into incentive mechanisms to support agriculture, fisheries, livestock, and sustainable forestry operations.

African agriculture suffers from a chronic lack of funding. Financing is one of the main obstacles to the growth of the agricultural sector, especially for small-scale farms. Only 10% of producers, usually those integrated into value chains for cash crops, have access to credit. Direct financing of rural activities has always been considered, in general, as costly and risky, and for this reason, it has remained very limited.

While financial products and systems have improved in many urban areas of the Global South, their availability lags significantly in rural regions. Money tends to flow toward money, rather than toward labor or land. It doesn’t flow most abundantly to the sectors and regions where it is scarcest. Consequently, financing tends to focus more on export cash crops (cotton, coffee, cocoa, rubber, etc.) and neglects domestic food crops, which are also in need of funds.

In general, agricultural and rural financing can be characterized by two institutional forms: those that start with the financial sector and its intermediary institutions (banks, microfinance institutions, insurance or guarantee funds) as the basis for organizing financial services and financial inclusion, and those that contract their financing articulated with the organization of agricultural and food value chains.

The recognition of the crucial importance of support for agriculture is stronger than ever. It is estimated that modernizing agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa alone would require an annual volume of capital of more than 200 billion euros. Agricultural financing policies should be re-legitimized to address the numerous imperfections in financial markets. Public and private funds, including those from development agencies, foundations, companies, and NGOs, sometimes carrying innovations, should be channeled into incentive mechanisms to support agriculture, fisheries, livestock, and sustainable forestry operations. This particularly includes investments that adhere to social and environmental criteria.

The position of the African Union Commission is now very clear: “Member States must focus more on this commitment by increasing public investments in agriculture. They must improve access to and use of financial services by smallholder farmers/rural households, who, in turn, will increase investments in the agricultural sector as they represent the largest and most important segment of agricultural value chains.”

The time is no longer for the formulation of general, overly normative policies regarding rural credit. Its future lies in the combination of diverse instruments and mechanisms, close to borrowers and savers, if not managed at least controlled by the stakeholders themselves, allowing for better adaptation of credit to various needs (production, but also small investments, consumption, social obligations) and in the development of a mutualistic spirit.

1. The Six Fundamental Questions of Rural Financing

The operational debating points number six. [2].

- Agricultural credit or rural credit? Credit operations mainly focus on agricultural production in the strict sense (input supply, equipment). The financial services offered are actually poorly adapted to the systemic and fluctuating nature of farmers’ needs, which include various types of crops, both subsistence and cash crops, various forms of livestock, and non-agricultural activities (processing, marketing, craftsmanship), following a schedule dictated by the seasons. Financial services for agriculture can only be effective if they are integrated into a rural economy supported by functional services: input supply for production, marketing, technical advice, dissemination of management models, market information systems, etc.

- Productive or unproductive credit? Social credits related to family needs (additional food, health, education, dowry, funerals, etc.) are always suspect due to the risk of non-repayment. Nevertheless, differentiation is not easy to make when unproductive credit acts as a stimulus to agricultural, livestock, or fishing activities.

- Hot money or cold money? Cold money comes from external sources, such as the government or donors; it is scarce and can be diverted or not repaid. Hot money, on the other hand, comes from farmers themselves, deserving careful attention and enabling social control. In Tanzania, for example, only 40% of rural residents have access to financial services, and among them, three-quarters obtain their loans from savings and credit associations or informal lenders, with very few having access to banking services. However, it would be erroneous to too systematically oppose official and informal financial sectors. Many links exist between the two: for instance, the sums allocated by rotating savings and credit associations to their members are often deposited in banks, as are monetary reserves accumulated after marketing.

Neighborhood tontine in Niamakoro, Bamako, Mali © Africa World Institute

- Individual or collective credit? Credit typically extends to the operator, but it is often guaranteed by a group or village. Savings and credit cooperatives, which emerged in Ghana in 1956 and later in Burkina Faso, Benin, and other West African countries, are associations of individuals, nonprofit, and with variable capital, based on the principles of unity, solidarity, and mutual aid. Their main purpose is to collect savings from their members and grant them credit. Today, the microfinance sector is growing rapidly.

- Market interest rates or administered rates? The cost of credit was partly covered by the state for decades with subsidized interest rates; the risk of non-repayment was limited by source deductions in controlled sectors. Today, interest rates are free but regulated. However, the interest rates offered, especially by microfinance institutions, are often not easily compatible with the level of profitability of family agricultural activities. In Niger, MFIs apply base rates ranging from 18% to 21%, to which filing fees and commissions averaging 1% are added. This is a limitation because exit rates must not exceed 24% in accordance with the usury law applicable to MFIs. Under these conditions, developers tend to favor administered credit rates, which are low for agriculture, and high interest rates for savings. This position does not guarantee the sustainability of the systems if credit is not collateralized by low-cost external resources: credit management is costly, and mutualistic systems must find resources to balance their operations.

- Centralization or decentralization? Public investment and vertical coordination of the economy by the state in the post-independence years are now giving way to formulas closer to savers and borrowers. They should be considered by their members as their own businesses. Decentralization does not prevent organization in networks and pyramids, especially for training or representation vis-à-vis authorities or banking structures.

In the area governed by the regulations of the Central Bank of West African States, Niger is one of the countries where access to financing is least developed, and this phenomenon specifically affects rural areas, particularly agriculture and livestock. The relative scarcity of financing in the rural and agricultural sector has not prevented the emergence of interesting experiences and initiatives arising from collective actions within producer organizations or federations.

The country’s financial system consists of 12 institutions and 42 decentralized financial systems (DFS), with 210 service points distributed throughout the country. Less than 17% of their outstanding loans are allocated to agriculture. Other credit needs are found in activities upstream and downstream of production, at the group, cooperative, or small rural business levels, namely: providing producers with input supply services (seeds, phytosanitary treatments, fertilizers, etc.), materials, and equipment; product valorization activities (packaging, processing, etc.).

2. A widespread deficiency

Small-scale farms are the primary source of income for over half a billion Africans, accounting for 65 to 70% of the population (over 80% in some countries). Yet, less than 3% of bank loans are allocated to them. According to the World Bank, an annual investment of $80 billion is needed to meet Africa’s food demand. Therefore, access to appropriate financial services is an essential requirement to unlock the potential of African agriculture.

© R. Belmin, CIRAD

In 2003, during the African Union summit held in Maputo, Mozambique, heads of state and government committed to investing 10% of the national budget in agriculture. This initiative, commonly referred to as the Maputo Declaration, is the primary instrument that leaders established when launching the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) to achieve an annual agricultural growth rate of 6%. This commitment has remained unchanged over time and has formed the basis for subsequent AU declarations on agriculture-focused development, such as the 2014 Malabo Declaration on Accelerated Agricultural Growth and Transformation for Shared Prosperity and Improved Livelihoods.

Two decades after the Maputo Declaration, very few countries have reached the 10% target. Five countries (Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Malawi, Mali, and Niger) consistently met the target between 1980, while Benin, Mozambique, Senegal, and Sierra Leone are countries that reached the goal only in certain years following the commitment. The share of agriculture in the continent’s total public expenditure has steadily declined over time, dropping from an average of about 7% per year in the 1980s to less than 3% per year on average over the last decade.

Regarding the indicator on smallholder farmers/rural households’ access to financial services and their use in agricultural transactions, the results suggest poor performance: only seven countries (Eswatini, Mauritius, Morocco, Nigeria, Seychelles, Tunisia, and Zimbabwe) were on track for access to agricultural services. Only sixteen countries scored 30% or higher on this indicator.

Certainly, the 10% numerical target may seem arbitrary. However, given that public spending on agriculture has a high return in terms of economic growth and that agricultural growth has been more effective in reducing poverty than growth from other sectors, the continued decline of agriculture’s share in total public expenditure in Africa is indeed concerning. The agriculture sector’s contribution to GDP has remained at around 15% on average across the continent since the 1980s, even though the sector is supposed to address challenges such as food security, malnutrition, poverty reduction, and resilience-building while dealing with issues like climate change, natural resource degradation, and the spread of pests and diseases.

Significant efforts are needed in resource allocation because there remains a gap between declarations and actions. The agriculture sector’s contribution to GDP on the continent ranges from 20 to 40%, yet the percentage of loans allocated to agriculture by commercial banks is only 3% in Ghana and Kenya, 4% in Uganda, 8% in Mozambique, and up to 12% in Tanzania (Source: MFW4A, 2023).

In a comparative study conducted in three West African countries (Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana), V. Ribier and J-J. Gabas[3] demonstrate that national institutions are still generally too weak to channel new financing flows toward their stated objectives. Financing disparities, already pronounced in the past, are exacerbated, and the overall increase in financing amounts tends to concentrate on entrepreneurial agriculture with high added value, rather than on family farming, public goods, and remote areas.

Are they the forgotten ones of financing?

3 to 5% of bank loans go to agriculture in Africa.

Drawing from Grain de Sel, No. 72, 2016.

The current architecture of agriculture financing is often “structurally incapable of supporting small-scale and local investment opportunities… It is archaic, inflexible, and organized in a way that prevents such enterprises and producers from thriving… Most tend to focus on a scale and mode of reproduction that are not suited to local environments” (Astone, 2018). How to transform financing to promote transitions to more just and sustainable food systems and enable agroecology to realize its full potential? This is the question underlying a research trend led by Coventry University (Center for Agroecology, Water and Resilience), the University of Vermont (UVM Institute for Agroecology), and AgroecologyNow!.

This deficiency prevents farmers from managing their naturally fluctuating cash flow or investing in intensifying their production systems. Financial services and credit offerings remain inadequate for short-term needs such as financing inputs (seeds, phytosanitary treatments, fertilizers, etc.), livestock fattening, or end-of-harvest storage; as well as medium-term needs such as equipment, mechanization, access to irrigation, energy, land acquisition, or herd rebuilding. Other credit needs are found in activities upstream and downstream of production, at the group, cooperative, or small rural enterprise level, including: providing producers with input supply services (seeds, phytosanitary treatments, fertilizers, etc.), materials, and equipment; product value-adding activities (packaging, processing, etc.).

Low levels of formal education and literacy complicate financial and commercial management information and advice, as well as the provision of proper planning documents for credit approvals. In general, farmers also have limited tangible collateral, and even in the case of mortgages on registered land and other real estate titles, it is often challenging for lenders to liquidate these assets in rural areas. Considering the often substantial distances involved, transportation costs, information collection, and other transaction costs are high.

3. The financing needs

In 2016, the African Development Bank estimated that the transformation of 18 agri-food value chains in Africa would cost up to $400 billion over 10 years. In 2020, CERES 2030, on the other hand, considered that eradicating hunger and doubling the incomes of small-scale producers would require $45 billion annually. In 2022, S.W. Omamo and A. Mill from New Growth International (NGI) proposed a new assessment of the required investment amounts to transform Africa’s agri-food systems with higher productivity and lower production costs to achieve a significant reduction in food insecurity. Based on the Food Systems Performance Index (NGI Index), the study estimates that the necessary transformation of food systems in Africa will require $76.8 billion per year until 2030, with $15.4 billion from the public sector and $61.4 billion from the private sector. Investment levels by country highlight the particularly significant needs of Ethiopia ($8 billion/year), Niger ($6.5), Tanzania ($6.1), Morocco ($5.4), Mozambique ($4.5), Mali ($4.3), Uganda ($4.1), Algeria ($4.1), and Nigeria ($2.9).

As shown in Table 1, the financing priorities that emerge from an analysis of public expenditures suggest a distribution across four levels of intervention for the entire continent. The needs for transformation and commercialization infrastructure are probably underestimated.

Table 1. Estimation of the allocation of annual public expenditures for food system-related interventions (low estimate).

Source: Omamo & Mills, 2022.

According to other assessments, the total value of annual investments required for agriculture and food systems ranges from $15 billion to $77 billion for the public sector alone. For the private sector, the total annual volume of investments needed to build sustainable agri-food systems could reach up to $180 billion. Its vital role is a common point among all methods of estimating financing needs.

The magnitude and type of financing required vary significantly depending on the key actors involved (Table 2).

Tableau 2. Financing Needs and Types of Providers by Types of Needs

Source: AGRA 2022. Report on the State of Agriculture in Africa. Accelerating the Transformation of African Food Systems (No. 10), Nairobi, Kenya, Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA).

IFD, development financial institution

IMF, microfinance institution

Capex, (short for Capital Expenditure) acquisition of tangible assets (land, equipment, tools…) and intangible assets (software, patents…) used for more than one year.

The determining factors for the success of a financing scheme are not specific to Africa: proximity to credit applicants, active listening, professionalism of agents, availability of tailored complementary services (advisory, training, risk management). However, above all, the lack of collateral is the most essential factor for expanding rural credit. Using land as a form of security is often difficult to implement, as financial institutions seldom manage to enforce their rights due to a lack of legal land tenure or appropriate judicial procedures. Nevertheless, changes are underway. The institutional landscape of agricultural financing is undergoing transformation. In addition to states that often fail to meet their commitments and traditional, uninnovative external aid, new actors have emerged: private foundations, venture capital funds, dedicated funds from development banks, incubation funds, leasing, refinancing lines, various facilities…, involving new private actors, particularly from Asian countries. Not to mention funds from diasporas.

At the same time, innovations in credit schemes are being deployed and are undergoing validation through significant experiments. In order to effectively expand financial facilities and strengthen agricultural financing systems, the approach includes “catalytic investments,” which are flexible and risk-tolerant funding, digital solutions, and alternative lending models.

4. Institutional financing

Are public agricultural banks emerging from failure?

In Sub-Saharan Africa, agricultural development banks, conceived as the strong arms of the states, were widely introduced in the 1970s as a significant means to promote economic development, wealth creation, and employment in rural areas. Most of them were state-owned and funded by governments and international donor organizations.

Public banks were criticized for their inefficiency, recurring deficits, and lack of transparency. Besides some of them being used for political purposes and falling victim to nepotism and corruption, many of these institutions faced significant issues, such as the absence of distribution networks and a focus on providing loans without offering savings options simultaneously. For these reasons, most of them were not in an institutional position to generate the expected effects and therefore achieve their initial goal.

Public authorities often imposed debt write-offs, fueling some confusion in the minds of farmers between grants and loans. The liquidation of the Bank for Agricultural Financing (BFA) in Côte d’Ivoire in 2014, ten years after its creation, confirmed the difficulties of such institutions. After announcing the creation of an agricultural bank in 2011, Cameroon finally abandoned the idea in 2018. In West Africa, only the Senegalese Agricultural Bank, the National Agricultural Development Bank of Mali, and the Agricultural Bank of Niger have remained.

The vulnerability of banks dedicated to agriculture is a well-known fact, common to all states. The low proportion of funding allocated to agriculture is explained by specific constraints inherent to this sector: high production risk (high likelihood of droughts, technical failures, phytosanitary attacks, or animal epidemics); market risks (price volatility, market instability) that can affect the repayment capacity of credit beneficiaries.

When banks target peasant farmers with little or no collateral, they declare exposure to default levels that are difficult to reconcile with the prudential rules set by central banks. Seasonal loans often have to be repaid in a single installment, knowing that producers generate monetary income only at harvest and do not always have intermediate incomes to make staggered repayments. When this single installment experiences repayment delays, such as unfavorable market conditions at harvest, banks are required to reclassify the outstanding installment and create a provision. On the side of producers, the distance to service points and the costs to access financial services are additional obstacles.

As only one actor among others in agricultural financing today, are agricultural banks expected to play a significant role in the future? In fact, since the 2010s, commercial banks have been cautiously opening up to family agriculture. Some are forming alliances with microfinance institutions that have decentralized networks capable of being in proximity to farmers. Given the significant risks inherent in agricultural activities, going beyond this will require improvements in financing instruments and guarantee mechanisms that can be coupled with digitization to facilitate the work of banks while reducing their costs.

On the sidelines of the “Dakar 2 Summit on Food in Africa” in January 2023, the African Development Bank Group and the Government of Canada announced the establishment of a fund for the growth of small and medium-sized agricultural enterprises.

Named the “Catalytic Financing Mechanism for Agri-food SMEs,” the new fund aims to catalyze and de-risk investments for agricultural SMEs, while strengthening agricultural value chains and improving food security on the continent. The Catalytic Financing Mechanism for Agri-food SMEs will contribute to achieving the goal of the African Development Bank’s Affirmative Finance Action for Women in Africa (AFAWA) program, which aims to bridge the $42 billion financing gap for women-led SMEs and accelerate their growth. This mechanism is the bank’s first mixed financing facility specifically targeting SMEs operating in the agricultural value chain. It mobilizes public funds to de-risk agricultural financing, provides support to SMEs to make them more bankable, and collaborates with capital providers to make banks more “agriculture-friendly.”

The other rural credit institutions and the limitations of microfinance

A wide range of options exists. Upon examination, the mobilization of agricultural organizations is often a strong prerequisite for building, on a territorial scale, a financing policy for family farming.

Rotating credit associations (tontines) offer an effective method for attracting small savings and providing small loans to rural households, often for consumption needs. The repayment performance is not ensured by formal guarantees but results from social pressure, and it is generally good. Indeed, the functioning of tontines appears to be well-suited to the African sociocultural environment: since the tontine represents an obligation of interpersonal solidarity, it can be validly opposed to other social obligations, especially family mutual assistance.

Mutual guarantee societies have a broader scope. They are established within a peasant organization or an economic interest group, which is common in West Africa. They are managed closely by their members, sometimes with employees. The approach for the concerned organization is to seek financing from a financial institution based on the needs of its members (improved seeds, fertilizers, insecticides, and phytosanitary products), while depositing financial collateral of up to 25% of the requested amount for managing potential risks. This credit, which has a maturity ranging from 6 months to 5 years depending on the financing objective, is used for acquiring agricultural inputs or equipment or for income-generating activities. Mutual guarantee societies allow for the generation of larger flows. Repayment rates of 95% to 100% have sometimes been recorded in experiences of solidarity-backed credit in West Africa. These high repayment rates seem to indicate that this microcredit is an effective and sustainable solution for deploying agricultural innovations (Traoré, Bocum, Tamini, 2020).

Credit unions provide loans, often without collateral, and sometimes borrow from official systems. They can be small or relatively sophisticated structures, such as the Credit Unions in Cameroon and Burundi or the People’s Banks in Rwanda. They aim to develop structured networks of cooperative members adhering to a federation, equipped with a central fund, and, in some cases, such as Rwanda, offering a wide range of services (insurance, mutual guarantee company, rural information).

Savings and credit cooperatives are the basic component of rural microfinance. They are based on community financial solidarity and can be found almost everywhere, from the Sahel to Madagascar. Examples of best practices are useful. Established in Niger in 1991, the Village Savings and Credit Associations (AVEC) demonstrate that there are alternative options. Members save at regular intervals and lend funds according to the conditions determined by the group. They have spread to 39 countries, mainly in Africa. They offer extensive opportunities to help young people save money to invest in agriculture and access credit, all while receiving support and access to information through a group. AVECs could help young people in rural areas get involved in both agriculture and non-agricultural sectors. In this case, what predominates is a security and distributive logic at the group level, within the framework of family or ethnic affiliation, in which each member has rights and obligations. These savings associations, which take the form of self-managed village savings and credit groups, often also serve as emergency funds.

Leasing companies occasionally provide their services to agriculture, for example, for tractors and machinery. So far, they have been rarely present in rural areas, with Equity for Africa financed by KfW in Kenya being one example. Leasing companies are not necessarily cheaper, but they reduce the considerable acquisition costs to regular and smaller payments, which must, of course, be synchronized with the seasonal cash flows in agriculture. For leased investment goods to serve as collateral, training must be provided, and a legal framework must be established. In addition, there must be a second-hand market for resale.

The rise of digital credit

Digital financial services from East Africa are increasingly disrupting the rural landscape. They are providing a growing number of countries with a gateway for delivering financial solutions to the “last mile,” where traditional financial services were limited due to infrastructure issues and economies of scale. Mobile telephony now, in some circumstances, offers the possibility of addressing some of these issues and extending access to financial services to remote areas.

The main categories of services offered by existing platforms are:

1. Mobile payments: Kenya was a pioneer in this regard with M-Pesa (which means “money” in Swahili), created in 2007 by Safaricom. It offers non-banked populations, the majority of whom are farmers, secure payment methods, avoiding the need to travel long distances with cash and providing access to other financial services such as savings and insurance. The volume of transactions processed is equivalent to that of all the country’s banks. In 2020, it had over 20 million users, which is one in three Kenyans.

2. Credit: The disbursement of a small loan can take only one to two hours with a mobile account. FarmDrive offers a Kenyan application that provides a credit applicant assessment tool. Applicants fill in information about their farming operations (land size, yields, inputs used), and based on this data, FarmDrive generates reports to confirm the future creditworthiness of borrowing farmers. These new tools are both risk management tools, including credit scoring based on satellite imagery, and mobile banking platforms (such as M-Kesho by M-Pesa in partnership with Equity Bank, for example).

3. Savings: Mobile banking payment applications usually offer a valuable savings service due to the seasonal nature of farmers’ income sources.

4. Index-based insurance: It uses satellite imagery to assess the consequences of weather-related incidents and triggers automatic reimbursements for insured producers located in areas affected by these incidents (e.g., Kilimo Salama). These technologies suggest the possibility of low-cost agricultural insurance potentially suited to Africa.

Mobile Credit, a platform that allows members of Rural Credit of Guinea (CRG) to carry out most of their operations from their phone, tablet, or computer, is at the center of the microfinance institution’s development strategy in the Forest Region of Guinea. Mobile Credit operates in 25 service points, including 21 kiosks and other service offices. The Forest Region has at least 159,000 CRG members operating in various sectors, including agriculture and commerce.

Microfinance institutions that support savings and credit cooperatives and mutual guarantee societies have experienced a gradual evolution, moving from the “empty” years of the pioneering phase to the “overflow” of recent years. Consequently, they face a series of major challenges, including an increase in the number of beneficiaries, growth in collected deposits, a rise in the outstanding loans, and the arrival of new actors such as public regulators, credit rating agencies, accounting firms, IT companies, and specialized training centers.

The most common criticism of microfinance is the high interest rates it offers. This is partly explained by the management costs associated with small loans. In the absence of a credit history and any collateral, this type of loan requires a more time-consuming evaluation to assess the borrower’s creditworthiness and subsequently to monitor and collect payments. This adds significant costs compared to the operations of traditional banks. The “ideal world of microfinance,” presented as a miracle solution against poverty, experienced a crisis in the late 2000s. With over-indebted clients, susceptible to the temptations of consumption, high default rates, and the arrival of new entrants with little concern for ethics, it became evident that unbridled growth combined with a vulnerable clientele had serious consequences for both clients and providers. In times of crisis, the microfinance sector naturally moves towards more regulation. This is manifested through the adoption of “best practices” and indicators aimed at assessing the conformity of their actions[4].

5. Value Chain Financing

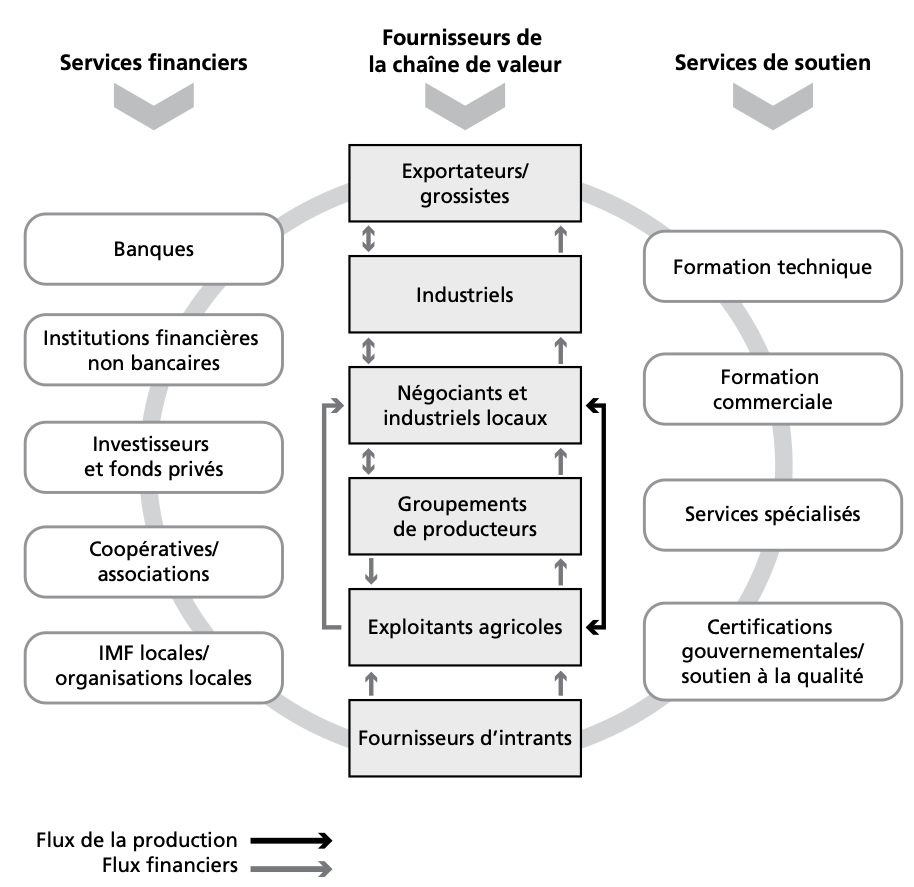

The role of value chain financing is to address the needs and constraints of all the actors involved in the chain, from farmers to input suppliers and buyers. Its tools can be used to 1) finance production or crops, 2) acquire inputs or products or finance labor, 3) provide overdrafts or credit facilities, 4) finance investments, and 5) reduce risks and uncertainties. It often meets a financing need, but it is also commonly used as a means to guarantee sales, procure products, reduce risks, and/or improve yields within the chain[5].

Production flows and financial flows within the value chain.

Within the chain, products flow in one direction, with different levels of added value at each level. Financial flows, on the other hand, move in two directions, depending on the type of chain and/or the region and dynamics generated by the involved participants. Financing is provided by all actors within the chain itself, such as, for example, an input supplier, and by various external financial institutions, as another example, a bank providing a loan to farmers based on a contract with a reliable buyer or a warrant from an approved storage facility.

Figure 1. Production Flows and Financial Flows in the Value Chain

Source Miller et Jones, 2013.

This type of financing is not new. Before independence, cotton producers in Mali and peanut growers in Senegal received seasonal credits from the then-public processing companies, while tea, coffee, and tobacco growers in Tanzania and elsewhere were financed through marketing boards.

Marketing boards were widespread in the 1960s and 1980s, often encompassing the entire agricultural development of a region. However, for reasons similar to those of specialized agricultural banks, they were very often inefficient and financially unsustainable, at least under the prevailing conditions. That’s why most marketing boards were abolished as part of structural adjustment measures. If they survived (for example, for cotton in many West African countries or cocoa in Ghana and Ivory Coast), their role and power were generally reduced.

In fact, the term “value chain finance” is used to address various situations: informal in-kind credit provided by input suppliers to a group of farmers, partial advance payment for future harvests by the buyer, farmer groups organizing to store their production to obtain credit from a microfinance institution, provision of services by private providers funded by buyers. Each of these situations falls under the term.

Innovations are an integral part of value chain finance development. It is essential to have a good understanding of the context, value chain processes, economic models, and financial and technological innovations that can be implemented.

The Warrantage System

Before the 1990s, the offer relied on three types of credit: compulsory savings credit, solidarity group credit, and project guarantee fund credit (Traoré, Bocoum, and Tamini, 2020). Later on, new credit variants with collateral constituted by agricultural product stocks were introduced. This is the case of warrantage credit.

Warrantage, or credit backed by stored stocks, has been booming in smallholder agriculture. It allows guaranteeing a loan up to 60% or even 80% of the value of a deposited harvest. Its operation is simple. After the harvest, the farmer deposits a certain quantity of their production with a storage organization (third-party storage) that attests to the existence, quality, and quantity of the stock and ensures its monitoring. The farmer receives a storage receipt (warrant). Subsequently, they can apply for a loan, which will be guaranteed by the warrant held by the lender. When the production is sold, the farmer and the buyer will go to the lending organization that will “release” the production. In practice, warrantage, a straightforward system, is most efficient when it is accompanied by the involvement of farmers’ organizations and microfinance institutions.

More and more experiences have seen small producers benefit from this system. The case of Burkina Faso is interesting. The company SEGAS has strived to establish a clientele among producer organizations. It operates in nearly 15 storage sites throughout the country. It receives goods, weighs and repackages them, treats them with an insecticide, and then issues warehouse receipts to depositors, allowing them to obtain credit from a microfinance institution. It also provides them with inputs and market research. Farmers are willing to pay SEGAS-BF twice the rate charged by their own producer organizations for third-party storage services. It adds value to the system by ensuring quality and providing greater flexibility and complementary services.

One of the great advantages of obtaining loans through buyers is that they are familiar with the requirements of sales markets, especially if they are active in crop production. Often, credit is part of comprehensive financial and non-financial service packages, including pricing or price-setting rules for the products sold. Everything is financed by marketing and its margins.

© Oxfam-SEGAS-BF

A Contractualization Modality

Contract farming agreements also exist within the private sector value chains. Due to the issue of parallel sales, they focus on certain cash crops for which there is a local private monopoly or where the product can be purchased at a higher price than the local market price (in niches such as fair trade or organic farming). Buyers with high investments and fixed costs (processors), highly perishable products (logistic costs), low availability in the free market (dependency on producers), or informed buyers (penalties for contract breaches, risk that contract non-performance leads to the end of commercial relationships) are also more inclined to engage in contract farming and provide credit. Alternatively, credit is largely based on trust, experience, and environmental protection within social networks. The multi-country survey mentioned earlier reports such large-scale credit for tobacco and partially for cotton, but otherwise, cash crops are not more frequently benefiting from credit than food products.

An example is provided by Umati Capital, a service company based in Nairobi that borrows the warrantage concept for its system. It offers two types of products: invoice discounting for large buyers and supply chain financing for smallholders and cooperatives. The company focuses on horticulture, livestock, dairy products, and grain and legume markets where there are relatively few well-integrated value chains. Its intervention allows a supplier, at the time of product delivery, to access 80% of the value of their invoice through mobile money at any time before they are paid by the buyer. Umati’s assumption is that the ability to get money upon delivery gives farmers a reason not to sell to traders outside the chain and to opt for a professional buyer who offers a better price and additional services such as input credit and extension services. Facilitating cash flows at the level of an aggregator such as a cooperative or processor has direct positive effects on the cash flows of the entire chain.

Five Key Points for Credit Applied to Value Chain Financing

- Actors – Suppliers, producers, buyers, and other value chain actors, due to their regular interactions, can better assess the roles and effective management of each other than a banker who interacts with them less frequently.

- Capacity – The assessment is not limited to the individual borrower’s capacity but is extended to the strength, reliability, and growth potential of the value chain and the competitiveness of all involved actors. Thus, the borrowing capacity of an individual borrower can be enhanced by their participation in a strong and reliable value chain.

- Capital – The capital of an individual borrower becomes less important in the context of value chain financing, as greater attention is given to capitalization within the entire chain.

- Guarantee – Cash and product flows that can be forecast based on relationships or contracts can replace or support traditional guarantees. In closely integrated chains, the guarantee offered by the strongest and most reliable partners can be used to attract financing, benefiting all other chain actors as well.

- Conditions – Financing conditions are better suited to a chain. Adapting financing to specific needs becomes fundamental to ensure its success and can improve clients’ ability to access banking services.Source : Miller (2008)

Diversified Offer

Upstream product and service providers can provide credit for the purchase of their products, often in kind. These credits are typically repaid during or after the harvest, sometimes through a pre-agreed source recovery when farmers are paid for their products. Specialized suppliers such as the fertilizer industry have a limited range of products that farmers need only in small quantities. However, they require various products and services at very specific times during the planting and growing season. Often, specialized agricultural traders or farmer organizations gather the necessary products and handle the “last mile” of delivery. Whether these intermediaries offer credit or allow purchases on credit depends on the financial capacity of the traders and the trust, transparency, formal legal security, and the ability to legally recover debts. Even in these local commercial relationships, social pressure plays a significant role in meeting obligations. Buying cooperatives reduce some transaction costs and offer better bargaining power. They can also compile customized product ranges from individual suppliers. Social pressure for payment discipline is considerable.

In Angola, microfinance institutions tend to consider farmers as high-risk borrowers. Frutos da Lagoa is a company trying to break this curse. Alongside Coopera, a local financial cooperative, they are running a pilot program to integrate small-scale farmers into an existing supply chain. Their joint business plan aims to prove creditworthiness to small farmers, enabling them to engage in large-scale fish farming. Frutos da Lagoa provides fingerlings, feed, and training to small farmers and then purchases the cultivated fish for processing. The solution is intended to be a win-win for all parties involved. Farmers have a buyer for their product, ensuring income and reducing operational risk. The financial cooperative achieves a competitive return on its capital, knowing that there is a market for its debtors, and Frutos da Lagoa has a guaranteed fish supply. The cooperative model ensures that these small-scale farmers have bargaining power when purchasing inputs. This system works because it removes the “uncertainty factor,” allowing farmers to focus solely on production.

What’s the verdict? “After examining various forms of credit, warrantage appears to be one of the most efficient and appropriate forms of credit in deploying agricultural campaign innovations, while credit on the solidary guarantee of commercial banks seems to be a viable option for promoting innovations requiring medium or long-term credit” (Traoré, Bocum, and Tamini, 2022, p. 89).

Many experiences are exemplary, but they are not universal. To function sustainably, value chain financing needs to be integrated into structured value chains, ensuring a satisfactory sharing of the value added among different actors. It is therefore selective when there is a high level of supply atomization. Furthermore, bank loans are often short-term, linked to specific value chains, and mainly focused on the downstream stages of the value chains (marketing and processing), which are likely more creditworthy than production. Finally, risk mitigation and profitability are essential considerations. In most successful cases, the public sector has always provided support, especially during the startup phase.

What to expect from the government?

Many empirical studies that have analyzed the determinants of agricultural innovation adoption have found a positive link between adoption and credit. However, the deployment of agricultural innovations through financial services always involves the intervention of multiple actors. Institutions must provide financial services, but producers must also meet the necessary conditions (collateral, organization, etc.) to access these services with the support of states and supervisory organizations (advice, training, cash flow management, partnership development, construction of storage facilities, etc.).

In terms of financing the agricultural economy, in addition to its regulatory role in providing a framework for credit and insurance regimes, the state increasingly has a role in providing incentives for the adoption of sustainable production models.

Its financial institutions are used in this context as vehicles for incentive measures, through interest rate subsidies or mixed subsidies for credits in favor of crop, fishing, or livestock systems that provide positive externalities.

The state can subsidize management advice, promote specific agricultural production, or cover part of the insurance premiums paid by farmers.

Regarding agricultural risk management, the division of roles between private actors and public policies is analyzed based on a risk segmentation according to its intensity and potential impact on farms. Risks of low magnitude are normally absorbed by farmers. The priorities of public intervention are more about encouraging farmers to adopt preventive measures (such as insurance and mutualization funds) and setting up safety nets against major climatic and economic hazards, the compensation for which is beyond the reach of private actors alone.

The agricultural sector is often shaped by strong regulations that must also be considered in financing. For example, this sector is more affected by government interventions in areas such as trade, food security, and the environment. Pricing policies for inputs and crops, as well as the choice of distribution systems, can significantly alter the prerequisites for agricultural financing, such as when prices are set on a territorial scale (reducing the risk of parallel sales), when trade policy stabilizes prices, reduces credit risks, or destabilizes them (increases credit risks), or when subsidies are distributed by the state (weakening the private sector) or in the form of vouchers for private distributors. However, overly strict regulation inhibits the development of entrepreneurship and institutional and organizational innovation. Financing inappropriate actors (non-viable, non-repayable) through government-led credit management, weakening repayment discipline, for example through debt relief for political reasons or the introduction of interest rates that do not cover costs, can lead production chains to inefficiency for several years or even lead to their collapse. This is not just a theoretical danger but a practice frequently observed for decades.

It is the responsibility of the state to play its role as a guarantor by establishing a stable regulatory and prudential environment.

In 2011, the Making Finance Work for Africa (MFW4A) Secretariat established a team composed of African stakeholders to identify agricultural finance policies and practices. Its policy recommendations led to the adoption of the Kampala Principles in June 2011, which are still relevant today.

- Providing “smart” or “market-aligned” subsidies to financial service providers and institutions that are essential for facilitating financial flows to the agricultural sector;

- Supporting the development of rural financial service providers, such as credit cooperatives (savings and credit cooperatives), which are often better equipped to mobilize and link local community savings;

- Providing partial credit guarantee and risk-sharing mechanisms to banks and other private lending institutions, in combination with technical assistance;

- Initiating a reform of existing public agricultural development banks to introduce independent management and lending decisions without political interference;

- Digital finance has the potential to expand financial services in the agricultural sector; however, regulatory frameworks should support ongoing digital initiatives while managing potential risks to protect consumers;

- Investing in physical infrastructure that supports the broader agricultural finance market, either directly (weather stations for insurance, irrigation systems, and warehouses) or indirectly (roads, railways, transportation, telecommunications, and power supply), especially in rural areas;

- Essential information includes climate data for agricultural insurance and transactional data between producers and buyers for value chain financing;

- Finally, establishing a specific high-level coordination body and recognizing a single entity as a promoter of agricultural finance can also have a positive impact.

Conclusion

In conjunction with the needs for food sovereignty expressed by many countries, the institutional landscape of financing African agriculture is undergoing a profound transformation. Alongside states that have long failed to fulfill their commitments and external aid often struggling to align with the needs expressed by farmers, herders, and fishermen, new models have emerged, involving new private and associative actors. Innovations in credit mechanisms are now unfolding, notably due to the expansion of mobile telephony, and they are undergoing validation through significant experiences.

Who will benefit from this? Will the provision of tailored financial services benefit all categories of farmers? To what extent will financial systems be able to promote the integration of small and medium-sized farmers into more productive value chains? The challenge remains to direct new financing towards priority targets for a more “inclusive” development than in the past, including family farmers, women, young people in rural areas, but also basic collective services. In other words, what financial service options will be offered to producers who are excluded from the services of institutional financial providers?

The era of formulating general, overly normative rural credit policies is over. Its future lies more in the combination of diversified instruments and mechanisms, if not managed, at least controlled by the stakeholders themselves, allowing for better adaptation of credit to various needs (production, small investments, consumption, social obligations), probably associated with the development of mutualism.

Bibliographic References

– Adjognon, S. G., Liverpool-Tasie, L. S. O., & Reardon, T. A. (2017). “Agricultural input credit in Sub-Saharan Africa: Telling myth from facts,” Food policy, n° 67, p. 93-105.

– AGRA 2022. Rapport sur la Situation de l’Agriculture en Afrique. Accélérer la transformation des systèmes alimentaires africains (n° 10), Nairobi, Kenya, Alliance pour une révolution verte en Afrique (AGRA).

– Arahama Traoré, Ibrahima Bocoum et Lota D. Tamini (2020), « Services financiers : quelles perspectives pour le déploiement d’innovations agricoles en Afrique ? », Économie rurale [en ligne], 371 | janvier-mars 2020.

– Astone J., (2018). Investing in food systems: Gaps in capital, analysis and leadership. [L’investissement dans les systèmes alimentaires : lacunes en capital, analyse et leadership.] https://swiftfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/2018-Astone-Investing-in-Food-Systems-1.pdf.

– Bradshaw, C.J.A., Ehrlich, P. R., Beattie, A., Ceballos, G., Crist, E., Diamond, J., et al. (2021), Underestimating the Challenges of Avoiding a Ghastly Future. [Sous-estimer les défis pour éviter un futur terrifiant.] Frontiers in Conservation Science 1 (9).

– Brulé-Françoise A., Faivre-Dupaigre B., Fouquet B., Neveu Tafforeau M-J., Rozières C. et Torre C. (2016). Le crédit à l’agriculture, un outil clé du développement agricole, Fondation pour l’agriculture et la ruralité dans le Monde (FARM), note n° 9.

– CERES 2030, 2020. Ending Hunger, Increasing Incomes, and Protecting the Climate: What would it cost donors? [Met fin à la faim, augmente les revenus et protège le climat : Qu’est-ce que cela coûterait aux donateurs ?] CERES 2030 Sustainable Solutions to End Hunger, The International Institute for Sustainable Development.

– Chiriac D. & Naron B. (2020). Examining the Climate Finance Gap for Small-Scale Agriculture [Examen de l’écart de financement climatique pour l’agriculture à petite échelle], Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), IFAD.

– Chiriac D., Naran B., Falconer A. (2020). Examining the Climate Finance Gap for Small-Scale Agriculture [Examen de l’écart de financement climatique pour l’agriculture à petite échelle], Climate Policy Initiative and IFAD.

– CIDSE. (2020). « Finance for Agroecology: More than Just a Dream? An Assessment of European and International Institutions’ Contributions to Food System Transformation » [Finance pour l’agroécologie : Plus qu’un rêve ? Une évaluation des contributions des institutions européennes et internationales à la transformation du système alimentaire.], Policy Brief [Note de politique].

– Coste J., Doligez F., Egg J. et Perrin G. [dir.], (2021). La fabrique des politiques publiques en Afrique, agricultures, ruralités, alimentation, IRAM Karthala.

– Doligez F., Lemelle J.P., Lapenu C., Wampfler B. (2008). « Financer les transitions agricoles et rurales ». In Devèze, J.C. (dir.). Défis agricoles africains, AFD/Karthala, 313-330.

– Doligez F., Perrin G. et Coste J. (2018). Construire des politiques agricoles sur des soutiens différenciés aux exploitations familiales viables, Enjeux et perspectives en Afrique de l’Ouest, IRAM et AFDI, Paris.

– FAO. (2018). Initiative de passage à l’échelle supérieure de l’agroécologie : transformer l’alimentation et l’agriculture au service des ODD. [Scaling up Agroecology Initiative: Transforming Food and Agriculture to Achieve the SDGs.] http://www.fao.org/3/I9049FR/i9049fr.pdf.

– Gasperi M. (2016). « Financement par et dans les chaînes de valeur : de quoi parle-t-on ? ». In Agriculteurs et accès au financement : quel rôle pour l’État ? Grain de sel, n° 72.

– Germidis, D., Kessler, D. & Meghir, R. (1991). Systèmes financiers et développement : quel rôle pour les secteurs financiers formels et informels ? OCDE.

– Guigonan A., Liverpool-Tasie S., Lenis Saweda L. and Shupp R., (2018). Chocs de productivité et comportement de remboursement sur les marchés de crédit ruraux : une expérience de terrain encadrée, Document de travail de recherche sur les politiques, n° 8528, Washington, DC, Banque mondiale.

– HLPE. (2019). Approches agroécologiques et autres approches novatrices pour une agriculture et des systèmes alimentaires durables propres à améliorer la sécurité alimentaire et la nutrition. [Agroecological Approaches and Other Innovative Approaches for Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems to Improve Food Security and Nutrition.] http://www.fao.org/3/ca5602fr/ca5602fr.pdf.

– Huet J-M. (dir.) (2021). Afrique & Numérique. Comprendre les catalyseurs du digital en Afrique, Pearson.

– Inter-réseaux (2016) Agriculteurs et accès au financement : quel rôle pour l’État ? Grain de sel, n° 72.

– Lapenu C. (2007). Évolutions récentes dans l’offre et les stratégies de financement de l’agriculture, Comité CERISE.

– McKague K., Jiwa F., Harji K., & Ezezika O. (2021). « Scaling social franchises: lessons learned from Farm Shop », Agriculture & Food Security, n° 10 (1), p.1-8.

– Miller C. & Jones L. (2013). Financement des chaînes de valeur agr

icoles, Outils et leçons, Rome, FAO et Centre technique de coopération agricole et rurale.

– Miller, C. et Amimo, J. (2021). Innovations et leçons en matière de financement des chaînes de valeur agricoles — Études de cas réalisées en Afrique, Rome, FAO et AFRACA.

– Mukasa, A. N., Simpasa, A. M., & Salami, A. O. (2017). Credit constraints and farm productivity: Micro-level evidence from smallholder farmers in Ethiopia, African Development Bank, (247).

– Ndiaye, C.T., Rietsch, C. & Sarr, F. (eds.). (2022). La microfinance contemporaine, les frontières de la microfinance. PURH.

– Omamo S. W. and A. Mills 2022. Investment Targets for Food System Transformation in Africa. NGI Technical, Nairobi and Chicago, New Growth International.

– Ouedraogo A. (2016). « Microfinance en Afrique de l’Ouest : histoire, défis et limites ». In Agriculteurs et accès au financement : quel rôle pour l’État ? Grain de sel, n° 72.

– OXFAM (2015). Warrantage paysan au Burkina Faso, accès au crédit par le biais des stocks de proximité, Rapports de recherche OXFAM, 61 p.

– Pernechele V., Fontes F., Baborska R., Nkuingoua J., Pan X. & Tuyishime C. (2021). Public expenditure on food and agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa: trends, challenges and priorities. Rome, FAO.

– Storchi, S., Hernandez, E. & McGuiness, E. (2020). Research and learning agenda for the impact of financial inclusion. Focus Note, CGAP/World Bank.

– Traoré A., Bocoum I. & Tamini L. (2020). Services financiers : quelles perspectives pour le déploiement d’innovations agricoles en Afrique ? Économie rurale, 371.

– Von Pischke J. D. (1991). Finance at the frontier. Debt capacity and the role of credit in the private economy. World Bank.

– Wampfler B., Lapenu C. & Doligez F. (2010). Organisations professionnelles agricoles et institutions financiers rurales. Construire une nouvelle alliance au service de l’agriculture familiale. Les Cahiers de l’IRC-Supagro.

– Wampfler R. (2016). « Pourquoi il est si difficile de financer l’agriculture familiale ? ». In Agriculteurs et accès au financement : quel rôle pour l’État ? Grain de sel, n° 72.

– Woodhill J., Hasnain S. et Griffith A. (2020). Farmers and food system: What future for small-scale agriculture, Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford.

Notes

[1] Commission de l’Union africaine, 2020. Rapport biennal à la Conférence de l’UA sur la mise en œuvre de la Déclaration de Malabo de juin 2014, Conférence de la 3ème session ordinaire, Addis Abeba, p.14.

[2] Cette typologie est inspirée par un article toujours d’actualité de Dominique Gentil, « Finances rurales : débats actuels et orientations méthodologiques », Techniques financières de développement, n° 27, juin 1992.

[3] Ribier V. et Gabas J-J., 2016. « Vers une accentuation des disparités dans le financement de l’agriculture en Afrique de l’Ouest ? », Cahiers Agriculture, 25, 65007.

[4] Un dispositif d’audit des performances sociales a été élaboré par le groupe CERISE (Comité d’échange, de réflexion et d’information sur les systèmes d’épargne-crédit). Lancées en 2012 par la Social Performance Task Force (SPTF), les Normes Universelles de gestion de la performance sociale (Normes Universelles) rassemblent dans un manuel exhaustif les meilleures pratiques visant à aider les IMF à mettre les clients au centre de leurs décisions stratégiques et opérationnelles, et à aligner leurs politiques et leurs procédures sur les pratiques commerciales responsables. Aujourd’hui, les Normes Universelles sont considérées comme la référence au niveau mondial en termes de pratiques rigoureuses de gestion de la performance sociale dans le secteur de la finance inclusive.

[5] La référence sur ce sujet est le rapport de la FAO et du CTA (Miller et Jones, 2013). Une autre étude complète sur ce mode de financement, assortie de 22 études de cas, est : FAO & AFRACA. 2020. Agricultural value chain finance innovations and lessons: Case studies in Africa, Rome. Voir aussi AGRA, 2020. Supply Chain Finance, a digital solution from Kenya, Nairobi, Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa.

[6] Les deux cas, Farmcrowdy et Frutoos da Lagoa, sont tirés de African Business, 2020. « African agriculture will not wilt in the face of covid », n° 476, août.